|

History - People - Alexander Mitchell Kellas

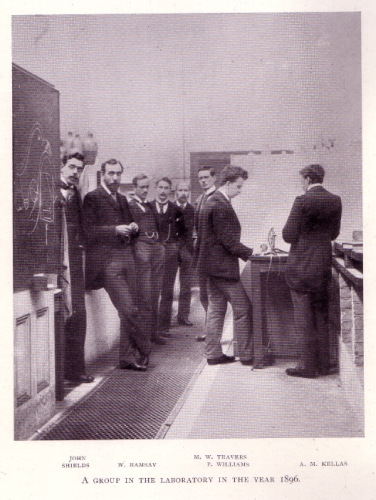

Do you remember getting bored in lectures in the Chemistry Lecture theatre and idly gazing at the names on the ChemPhysSoc Presidents boards? Dalea Larsen (1990) sheds light on the question.. The names on the ChemPhys Soc boards are something of a whose who of the Department and a mildly amusing time can be spent trying to spot names that are missing. Yet the early names are increasingly mysterious. Some are physicists, of course, going back to the days when the two departments ran a joint society. Others on the other hand are more obscure and Edgar Anderson recently discovered the identity of one of them while browsing one of his favoured subscriptions, "The Scots Magazine". Alexander Mitchell Kellas appears on the boards as CPS president 1897-1898 and until recently nothing was known of him in the department. Born in Aberdeen in 1868, Kellas studied at Edinburgh and Heriot-Watt, and then came to UCL as an undergraduate, where he got his BSc. in 1892. He went to Heidelberg in Germany for his PhD but returned to work in Ramsay's lab during the heady days of the discovery of noble gases. In his Nobel Lecture, Ramsay mentioned that "Kellas, working in my laboratory, and Schloesing, in Paris, had independently determined the amount of argon in the air; they found almost identical numbers - 0.01183 (Schloesing) and 0.01186 (Kellas) part by volume in 1 part of atmospheric nitrogen." The work was never published independently under Kellas' name, however. [Kellas is pictured at right in a Departmental photograph from about 1897.]

By 1900, Kellas had been appointed to a lectureship at the Middlesex Hospital and he was highly regarded there as a teacher of chemistry, writing three textbooks on practical chemistry. His first love was, however, mountaineering, and like Norman Collie he devoted much of his spare time to climbing and exploration. He went to the Himalayas seven times between 1907 and 1920- criss-crossing Kashmir, Nepal, and Sikkim photographing and mapping. He seems to have travelled mostly alone or with local porters, and made some notable Himalayan first ascents. In mountaineering circles, Kellas is often remembered as the first to recommend the use of sherpas in climbing expeditions, and at a time when it was not very common to do so, held them in very high esteem. It must have been during this time that he began to wonder about how the human body copes at high altitudes - some textbooks of the day even stated categorically that human beings could not survive above 21 500 ft (7200 m) - as he himself had spent more time above 20 000 ft (6500 m) than any other westerner before him. Back in London, he joined forces with the British physiologist J. S. Haldane (father of the UCL biochemist and geneticist J. B. S. Haldane) to carry out experiments on the effects of high altitudes on humans. The experiments, which they carried out together over a period of four days in a low pressure chamber at the Lister Insitute were reported in a paper (J Physiol. Lond. 1919-20, 53, 181-206) that makes for some amusing reading. Kellas coped with the reduced pressure rather better than Haldane. It was around this time that Kellas wrote his most important piece of work "A consideration of the possibility of ascending Mount Everest" in which made a series of remarkable predictions concerning the feasibility of climbing to the Earth's highest point without extra oxygen. His final conclusion that it would indeed be possible was not proven until 58 years later by Reinhold Messner and Peter Habeler.

In the run up to the expedition in the spring of 1921, Kellas and some sherpas made an attempt on Kabru, a fearsome 7338 m peak which remains unclimbed to this day, with a view to getting photographs of Everest and surrounding peaks. Returning, he had only nine days rest before the Everest expedition set out for Tibet. The trek proved exhausting and several members of the expedition, including Kellas developed severe diarrhoea. He became so ill that he had to be carried, but remained cheerfully stoic. Mallory recorded that "The old gentleman (such he seemed) was obliged to retire a number of times en route and could not bear to be seen in his distress and so insisted that everyone should be in front of him". A few days later, Kellas died of heart failure at the age of 53 and was buried in the village of Kampa Dzong, ironically, the first point from which Everest became visible to his colleagues. It is perhaps best to leave the last word to the great explorer and Himalayan mountaineer, Francis Younghusband "This Scottish mountaineer had, in fact, with the pertinacity of his race, pursued his heart's love till he had driven his poor body to death. He could not restrain himself." In his honour a 7113 m summit 12 km to the north of Everest was named Kellas Peak.

For more information on Kellas see Prof. John West's excellent article "Alexander M Kellas and the physiological challenge of Everest" J. Applied Physiology, 1987, 63, 3-11. A biography of Kellas by Ian Mitchell, containing much new material and newly discovered photographs, is due to appear in 2010.

This page last modified 20 September, 2010 |

Six days after submitting the manuscript to the Royal Geographical Society (which in fact never actually got round to publishing it) he left for India. By then he had resigned from his position at the Middlesex, which he had found increasingly stressful, and could therefore devote all his energies to the Himalayas. He joined an expedition to Kamet, a 7700 m peak on which he hoped to test oxygen equipment and carry out further measurements. The expedition was not a great success. The mountain was too tough and the experimental equipment unreliable. However, on his return to Darjeeling, he was thrilled to discover that the Dalai Lama had for the first time given permission for an expedition to enter Tibet and explore the Everest approach route from the North. In addition, as one of the leading experts of his day on both the Himalayas and on high altitude physiology, he had been invited to participate in this reconnaissance expedition which was to include George Mallory.

Six days after submitting the manuscript to the Royal Geographical Society (which in fact never actually got round to publishing it) he left for India. By then he had resigned from his position at the Middlesex, which he had found increasingly stressful, and could therefore devote all his energies to the Himalayas. He joined an expedition to Kamet, a 7700 m peak on which he hoped to test oxygen equipment and carry out further measurements. The expedition was not a great success. The mountain was too tough and the experimental equipment unreliable. However, on his return to Darjeeling, he was thrilled to discover that the Dalai Lama had for the first time given permission for an expedition to enter Tibet and explore the Everest approach route from the North. In addition, as one of the leading experts of his day on both the Himalayas and on high altitude physiology, he had been invited to participate in this reconnaissance expedition which was to include George Mallory.